The World of Shadows Come Alive, Part 1/2

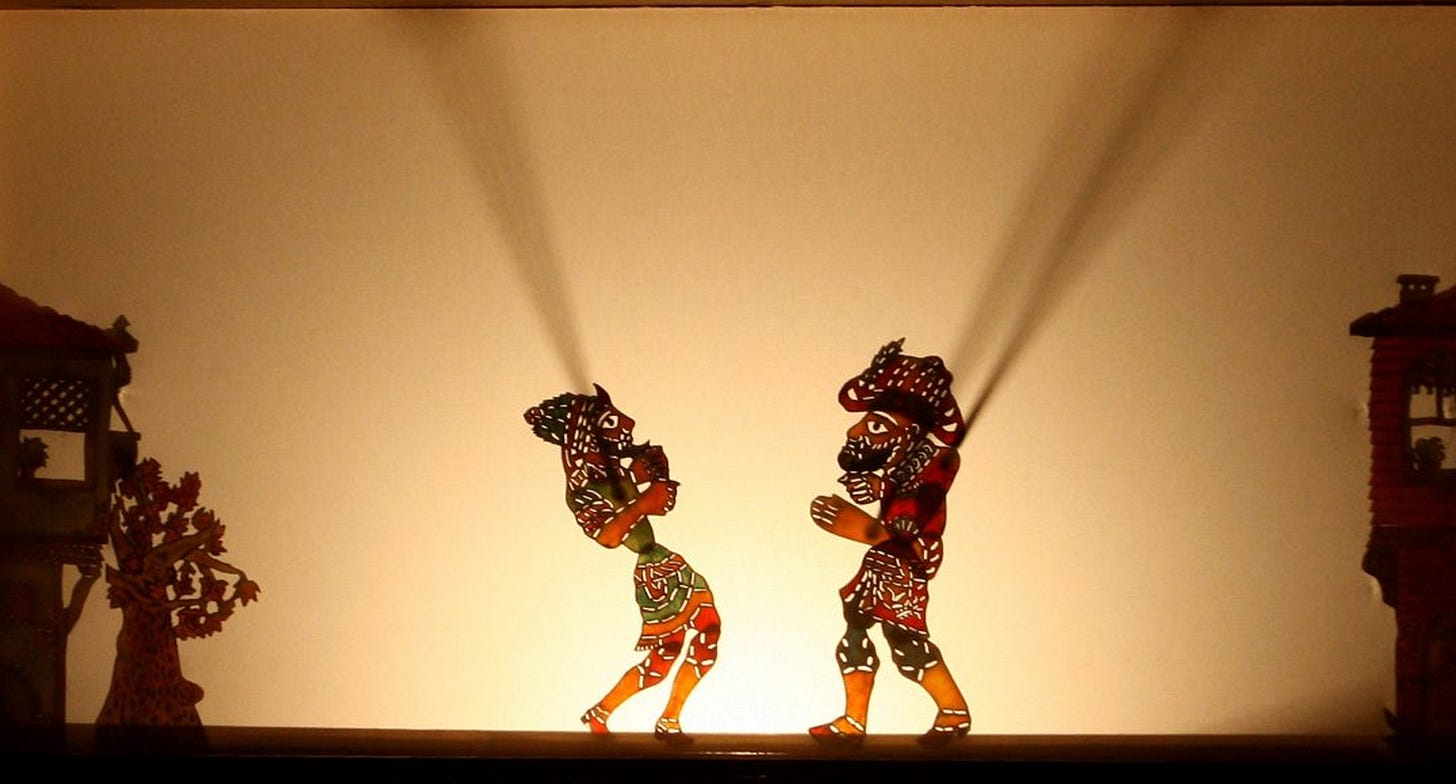

Translation of the first half of Haljand Udam's essay "Elustunud Varjude Maailm", which explores the art of shadow puppet theatre as seen through the Arabic and general Traditional worlds.

Part 2 of the essay, which investigates shadow puppet theatre in Indonesia as well as the impact left by shadow puppetry on Antonin Artaud, may be read here.

Puppetry in the Mediaeval Arabic World

Omar Khayyam in one of his quatrains has generalised puppet theatre as a rather sombre reflection of the entirety of the cosmos and Man’s existence:

We are puppets, with the firmament being our master —

truly it is so, we’re not faced with an allegory.

On the carpet of being he allows for us to play,

and after the play a place in non-being’s tomb awaits.

This ruba’i was written during the first half of the 12th century, but unfortunately we’re no longer able to fathom the appearance of the puppetry which stood before Umar’s eyes during the aforementioned quatrain’s creation. Our knowledge of the Middle East’s puppetry tradition originates from a much later time — from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th, when this art form had been relegated to the peripheries of culture — the chaos of the market. Such was the Turkish shadow puppetry karagöz and its variants in Arabic lands, chiefly the Egyptian xajāl az-zill, the main functions of which were the illustration of leisurely tales, often descending into banality, at bazaars or coffee houses by means of the performance of flat puppets fashioned out of camel hide. Although texts of shadow puppetry in Egypt have been preserved from the beginning of the 13th century, authors who prioritised a more critical audience simply disregarded them. Puppetry has not been the subject of philosophy since the time of Khayyam. However, another quatrain wherein the world is compared to a magic lantern — a device used for the projection of shadow images — has also been attributed to Omar Khayyam.1

But lone theatrical props may also have taken on the meaning of philosophical metaphors. The most meaningful has without a doubt been the veil, linen screen or curtain — surely this image has also been derived from shadow puppetry, wherein it bears ambiguous connotations. The curtain in shadow puppetry does not only hide and conceal, but also reveals — although not truth itself, but merely its shapes and variants. In some respects the viewer of shadow images resembles a dreamer who, in his senses, experiences only the perceptible half of reality, and cannot know what reality really is like behind the veil of experience and perceptibility. Omar Khayyam’s stance on the possibility of solving this problem was pessimistic:

Neither me nor you grasp the secrets of eternity,

neither me nor you comprehend its riddles,

wisdom we confer only on this side of the veil,

neither me nor you shall discourse once the veil goes.

Khayyam holds that Man himself is made out of the substance of shadows, and upon having reached the light behind the veil, he ceases to exist entirely. He was convinced, similarly to the mediaeval nominalists of the West, that we shall not know anything about supra-natural ideas and that it is likely such ideas do not exist in the first place, with everything coming to be only on this side of existence. Their origins are to be found in an otherworldly emptiness and non-being, wherein shadows are indiscernible from light.

However, the veil of shadow puppetry does not only conceal, but also exposes and reveals. Such a dual natured meaning gives ground to the much more optimistic stance of Abd ar-Rahman Jami (1414-1492), as attested by the following quatrain:

Here truth is the source of a thousand things

and gives them faces in innumerable amounts.

The doubtful may say the world’s a mere dream —

but in this reverie to us the truth is shown.

In some inexplicable but real manner, one who watches the shadows participates in the great play of ideas, essences and archetypes which are concealed behind the veiled world. The perceptible and imperceptible worlds are not separated from each other by an insurmountable border. Rather, the imperceptible is a continuation and extension of the perceptible and supra-natural world; the things in the perceptible world convey a message from the supra-natural domain. In the words of Plato: as the viewer watches the shadow, things which lay behind the veil are remembered by him, because he has once dwelt among them. Whether or not Man can understand the message conveyed by the shadows and is capable of reading into their contingent language is dependent on “the veil on his heart”.

Drama as Traditional Ritual

As understood by traditional culture, Man never observes the drama of life as a spectator — he always assimilates the observed play and is himself if not the protagonist, then at least one of its performers. Man has most profoundly perceived himself as a participator in ancient ritual, whence spectacle, which has not yet been transmuted into mere entertainment, is derived. One of the most frequent developments of ritual has been the staging of plays depicting myths and traditional epics. Unfortunately, ritual turns to performance only when the ritual in its original form is no longer needed, or when newer rituals have emerged, or when the need for it has receded entirely. But for quite a long duration such theatre continues to embody two meanings: it is no longer a serious ritual, yet not a means for passing time either. Though no longer initiating, it is still teaching existentially important knowledge.

Myths and traditional epics usually tell of the creation of the world and events carrying archetypal meanings which take place in the world’s early beginnings. In ritual the myth becomes alive, its participants leave their present state and return back to the beginning of time, which in some sense is another way of referring to the supra-natural reality. During the beginning, when everything had just been created, the world was good and in a state of perfection; later, with the passage of time, the world and Man decays. In other words — the unfolding of time is a struggle between good and evil. With the world becoming ever so distant from the beginning, so too does evil start to grow within it in ever-increasing quantities. For it to be possible to continue living, good must triumph over evil once again. A man participating in a ritual conjures himself into the beginning of time and equates himself with his ancestors who lived during the beginning, thereby renewing himself and coming to possess a magical force with which to rejuvenate the world around him. The act of departure from the present state and becoming a being of another world contained within the ritual is also emphasised by all other external signs which allude to a transfiguration into another being, chiefly the changing of dress and the mask.

In the second half of the essay Udam shall use the example of the shadow puppet theatre native to the Malay archipelago of Indonesia to show us an example of the art form practised in a traditional setting, concluding with the imprint such shadow puppetry left on the French dramatist Antonin Artaud.

References

Т . А. Путинцева. Тысяча и один год арабского театра. Москва, 1977, pp. 80-102.

Oh I loved this read! Thank you for sharing, reading the second part now!